I spent a lot of time last year writing about what’s not working— systemically, in the economics of small business— and while a few friends jokingly accused me of being a real downer, it needed to be said and, anyway, writing my way through a summer of failure wasn’t really a doom-spiral. It was mostly about noticing hopeful action sprouting through the cracks.

If you know even a little bit about my work, it’s probably obvious that I spend a lot of time thinking and dreaming about world building, and specifically building world’s of interdependence, regeneration, and care.

World building, in the counter-cultural context, is about creating an alternative (and usually subversive) reality. An articulated whole based on a set of values that point us away from the status quo.

Worlds are complex systems. They are made up of relationships, and encompass more than I can imagine by myself. World building involves creativity and imagination — an opportunity to think and dream outside of what we know. And also contending with all the messiness of systems and people, the dishes and the dust bunnies.

World building, within the scope of our own lives is also a way of practicing revolution:

“A revolution on a world scale will take a very long time. But it is also possible to recognize that it is already starting to happen. The easiest way to get our minds around it is to stop thinking about revolution as a thing— “the” revolution, the great cataclysmic break— and instead ask “what is revolutionary action?” We could then suggest: revolutionary action is any collective action which rejects, and therefor confronts, some form of power or domination and in doing so, reconstitutes social relations— even within the collectivity— in that light. Revolutionary action does not necessarily have to aim to topple governments. ” — David Graeber, Fragments from an Anarchist Anthropology

I spoke with Sarah Ryhanen late last year in a conversation that came out on the podcast a few weeks ago. It’s a conversation that, to my delight, has really gotten under my skin. In as sense we were talking about the very mundane work of revolutionary action, and our conversation has been a helpful one to think alongside.

Sarah is most known for her floral and soap empire, Saipua. I’ve been following her on the internet since her days as an industry leading florist in Brooklyn. Many seasons later, she now lives in rural upstate New York on World’s End Farm, which houses Saipua’s soap factory, helmed by Sarah’s mother Susan, and a new, communally organized, inter-generational school, The Worlds End School of Thought, Agriculture and Craft. A site of revolutionary action, for sure.

You can and should listen to our entire conversation, and below I’ll work through a bit of what we spoke about around labor, alienation, and value.

A World of Unalienated Labor

“How do we make our small corner of the world healthier, more fulfilling and more fun? How do we share what we know and inspire people to engage in world-building experiments that might provide alternatives to current systems which no longer serve our needs and desires? How do we learn to notice the immediate physical world around us, locate ourselves in it’s complex cycles, and practice tending to relationships with people, plants, animals and earth?” —via the World’s End Website

In the interview I started by asking Sarah to tell me about Saipua and World’s end in their current forms, and perfectly, she started by describing the view out her window.

She also spoke of communal breakfast, chores, the travails of democratic decision making, and about creating beautiful objects for their own pleasure first and foremost. World’s End Farm includes a flock of Icelandic sheep, whose wool is shorn, spun, and turned into garments: “we do it for ourselves, first and foremost. And that is the most important guiding principle of this place. I don't make wool because I want to teach other people how to make it. I make it because I love to make beautiful wool garments for myself.”

We didn’t name this explicitly in the conversation, but it occurred to me later that Sarah was describing “unalienation”, an unwieldy word1 to describe an elegant process of reacquainting ourselves with the fruits of our own labor.

The process of alienation turns people and things into wealth building assets. To do so, people and things are removed from their entanglements and ecosystems— from relationships. A person working in garment production produces sweaters shipped across the country to anyone with a web browser and a credit card. There’s a sheep in there somewhere, but no one involved could tell you its name.

One of the reasons I look so often to food or farming— any sort of land based business— as a locus of revolutionary action, is that these spaces of tangible nourishment are the perfect cauldron for transforming value.

And then we also talk constantly about new value systems. And I think the beautiful thing about a land based business is that you… start to see all kinds of different economies all around you.

And that really helps, I think, to sort of imagine a new future where we don't have the kind of economy that we're used to.

I’m sure that World’s End could sell sweaters if they wanted to, and I’m equally sure that there would be no way to adequately price such a sweater. But value doesn’t just mean price, and the kinds of entanglements that World’s End spins exist outside of the narrow confines of value as price and money.

However, without digressing into grisly details, pretty much every example of a project existing outside of monetary exchange that I can think of is… a cult. And even cults usually sell something.

“Membranes to capture value”

I wrote about world-building businesses a bit late last year:

Specifically I wrote about where a world-building project meets the marketplace, and what a dicey place that can be.

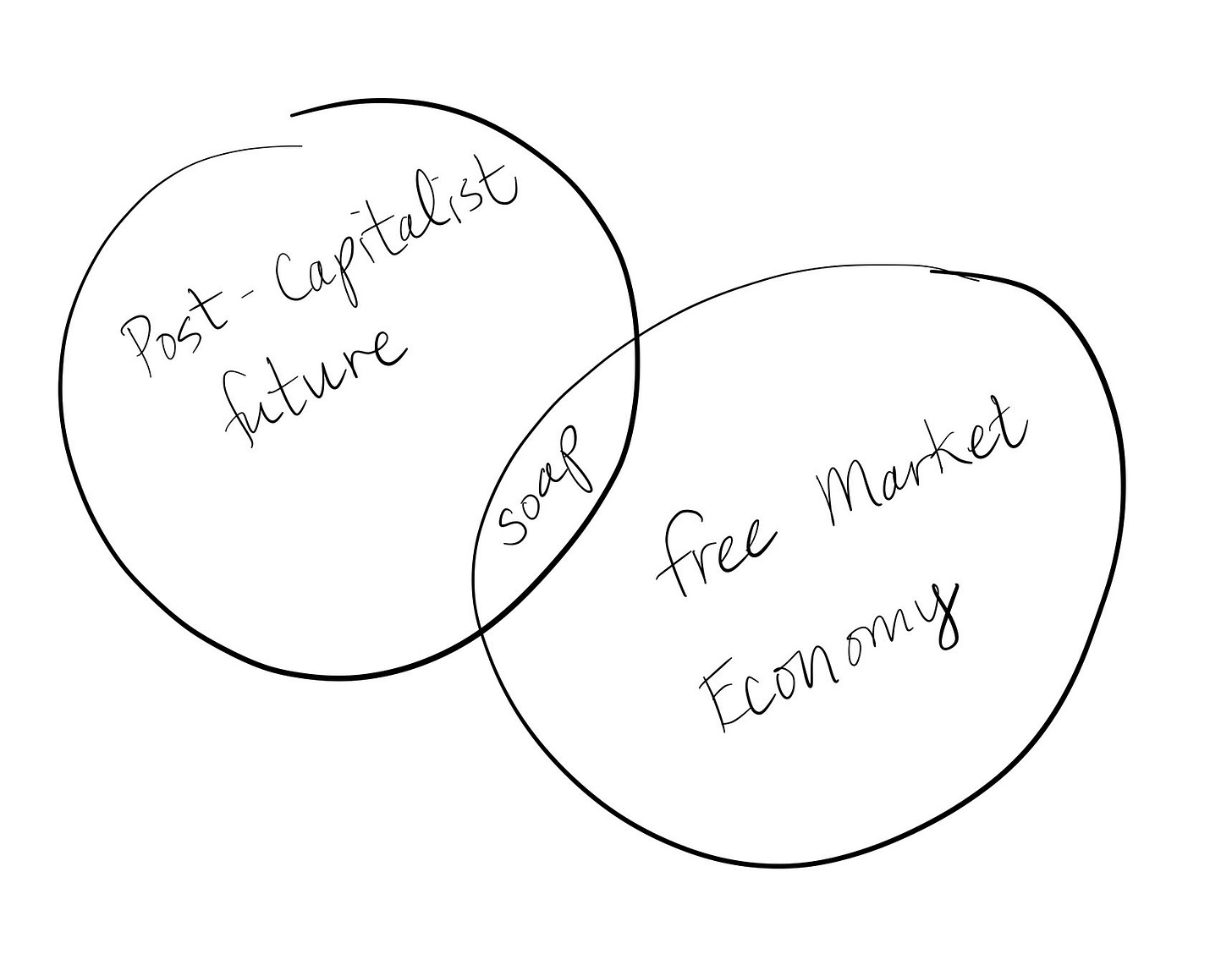

Dicey because we’re inhabiting conflicting value systems: there’s the capitalist market economy and then there’s the world that might center values of joy, mutualism, needs-meeting, and care.

Hopefully we’re all clear by now that the Capitalist money economy exists in opposition to real human and ecological needs. But, since we’re still living in a world where rents must be paid, that means “stealing” value from the current system to build and inhabit the new one.

This should be familiar territory for artists and creatives of any stripe.

Sometimes the term “sell out” gets thrown around to describe those of us that make money from our creative work or world building practices, but I want us to think about this differently, as a process of transmutation and alchemy. Of turning— in a near-literal way— gold back into the realm of ecosystems and relationship entanglement.

Theorist Michel Bauwens described this process as “[creating] membranes to capture value from the dominant system, but then to filter it and use it in different ways.”2

For World’s End, this is the the soap, the sale of which provides the backbone of funding for other activities, and ultimately in support of humans working outside of a monetary value regime. Interestingly, Sarah unhesitatingly named the soap as the thing she would chuck out the door in her utopian future.

Since the money economy has a way of taking over— Capitalism as a system seeks to subsume all forms of value as commodities— our value membrane needs continual tending.

You’ll know you’re tipping too far back into the marketplace when you start counting: pricing, optimization for profit. Because we’ve been indoctrinated in seeing the free market economy as a rational place (spoiler alert: it’s not), systems of exchange outside of that frame often look highly irrational! What rational capitalist would tend a flock of sheep, spending hundreds of hours to create luxurious sweater only to gift it to a friend??

Economies of Beauty + Joy

The soap is not just any old product or a way of making as much money as possible. It’s phenomenal soap3. The ingredients, the lather, the smell, the packaging: all thoughtful and of the highest quality.

There’s a value beyond the price, maybe we call it beauty, that connects to the values of the farm; it’s also the object that most readily lends itself to scale and a profitable business model.

Which means that what started as Susan's hobby has grown into a business that requires relentless marketing to sell. When Sarah said she’d chuck the soap in her ideal future, I took it to mean she’d do without the pressure of the beauty industry and the way that Capitalist values impact even the most beautiful things. We revolutionaries will still need to wash ourselves.

And rather than a future of gritty, grey, insipid soap why wouldn’t we imagine a future of the most gorgeous soap we can conjure?

To circle back to revolutionary action: I wanted to think alongside soap because it holds values of beauty, values of pricing and money, and in those multiple use values also provides a source of support for revolutionary action.

Because it’s not just a soap business4. It’s one facet of a larger world-building project. The piece that takes value from the monetary economy and turns it into communal dining, land management, nourishment, beauty, and probably a lot of tedious governance meetings and debates about democratic decision making.

Related Notes

- . Charlie describes himself as a reformer, but I am lobbying for viewing his work as subversive and revolutionary. Our conversation centers around the question of how groups of humans can work together in communities of care and how we can shift power. Listen here.

I’m really enjoying

’s writing on loneliness policy and social cooperatives— cooperatives where the profits do not solely benefit the workers, but also funnel back in to support the enterprise, like a non-profit.

Interestingly, while this is a real word…there isn’t really a common or succinct economic term to describe re-entangling oneself or reversing the effects of Capitalist alienation. (If I am wrong about this, please reach out and tell me otherwise!)

From Reimagining Value: Insights from the Care Economy, Commons, Cyber-Space, and Nature, David Bollier

Saipua’s extraordinary soap is my own secret gifting “weapon”. My family does a secret santa for the holidays and one of my quiet triumphs was the year I conquered the legendary ungiftable family member. Legend has it that this person blithely throws most gifts in the trash! Well my friends, I cracked the ungiftable with Saipua soap. They travel often and keep it in their luggage (according to Sarah, the soap has a shelf life and you shouldn’t do this, but it smells amazing and you would too), and exclaimed in front of many astonished familial witnesses on how much they loved it.

For more on businesses that do more than just “business”, I wrote a whole zine last year.