A Proposal for Partnership Profit

An elegant way to sidestep a whole lotta friction.

Greetings! This is a Boss Talks edition, and a long nerdy one at that. (Also two new Whiskey Fridays podcast episodes). I’ve turned comments on for all for this one, because I would love to hear your questions or thoughts. Thanks for reading!

John and I just released our 3rd episode in a little Whiskey Fridays series on Business Partnerships, where we take on the D-word: D-I-V-O-R-C-E.

Today though, I’m circling back to something that John, a true friend, generously teed up for me to talk about in the last episode on partner wonkiness and changes: a proposal for approaching profit and equity within a partnership that sidesteps a whole patch of thorny issues related to valuation and contribution. It happens to be very relevant for dissolutions too :)

As I say in the Wonkiness episode, I take for granted that partnerships will change in the lifetime of a business, so why not set yourselves up for handling inevitability with as much grace and elegance as possible?

What follows is an approach that borrows practices from the worker co-op world. I’d love to see someone try it! John texted me last week to let me know he pitched it to a client as a possible path.1

It’s also, as I’ll circle around to, a provocation and paradigm shift that may, for many of you, resolve some discomfort around the fundamentals of ownership and treating a business as an asset from which to extract value. (Others, it may piss off.)

Shared Wonkiness.

With the kinds of companies we work with, most partnerships start out 50/50 for duos or thirdsies for trios, even if it’s not explicitly laid out in an operating agreement. When value is contributed via expertise and a lotta work, and not capital, this usually makes sense.

But then, of course, inevitably “things” will change over time. Many types of changes lead to uneven contributions to the business. Hopefully you’re not avoidant and choose to do something about the wonkiness coming up.

That something, if you’ve acknowledged the uneveness might mean those even equity splits and distributions don’t quite make sense anymore.

Let’s imagine a couple of scenarios:

ONE

You and I have been running a successful business together for a number of years. We’re past the grind of getting started, and things are starting to feel comfortable. I decide it’s time to start a family, and I want to step back a bit after the kid comes along. I’d like to work part time, so we figure out a specialized role where I work about 10-15 hours a week. We reduce my salary, we increase yours and you step up as more of a CEO role than you’ve had before.

We get to the end of the year and, WOW, we’ve had a good one. Profit distros are looking cushy. Good job, you.

Me: working a scant dozen hours a week, ecstatic, living the business ownership dream.

You: the CEO working more than ever, hear the sound of screeching tires, a monster truck called unfairness mowing you down.

50/50??? You just worked your ass off for our best year yet, and I get half.

Not so fair, right?

TWO

You leave your old company at the same time as a couple of your coworkers, start a scrappy new company, and things take off pretty fast! Within the first year or two you find yourselves hiring, and even inching towards your bigger agency salaries. But…it’s become clear that partner #3 is along for the ride. Even worse, one of your best employees quits because, well, this dude is also an asshole.

So you and partner #2 get together, talk to a lawyer, and ask coasting asshole partner to leave. And he’s like, sure thing, PAY ME.2 Cue extended negotiations with a recalcitrant asshole and acquiescing to a buyout agreement that you know the agency can’t really afford, but at this point you just need that fucking guy to go away before more employees walk.

I could keep going all day here with other scenarios, but these two give you a good idea of two (super common, I can think of multiple real examples falling into both buckets!) types of friction.

When roles change, how do you ensure some sense of fairness? Or avoid relinquishing a whole lot of profit to make a bad guy go away?

It’s actually really, really hard to figure this out because the basis of a partner’s equity isn’t one thing.

In the first scenario, if you’re me, you’re like, hey, I put in my time and friggin earned this profit! If you’re you, the hardworking CEO, you’re like, whoa, wait a sec. What about our uneven ongoing contributions?!?

And we’re both right!

Our equity splits and how we distribution profit, in a vanilla partnership, are related to both our past contributions and our current and future efforts. But we don’t have an easy way to make adjustments over time.

The proposals I’m going to walk through draw on common worker-cooperative practices which — if I do say so myself— provide elegant solutions to the messy and conflict-ridden process of understanding equity and what a business owes you. It’ll also just happen to undermine how we think of businesses along the way ☺️

First, an as brief as I can manage explanation of worker cooperatives

This is a proposal for regular partnerships, but it’ll help to understand a bit about Worker Cooperatives to grasp what I’m talking about.

Worker Cooperatives describe various structures of business where the people who work in the business also own the business. They can be small— 3-4 worker owners— or include hundreds of workers.

Two key characteristics of worker co-ops3:

Workers own the business and they participate in its financial success on the basis of their labor contribution to the cooperative (ie, workers are entitled to profits).

Workers participate in governance structures and decision making via the principle of one worker, one vote.

In other words, profits and decision making power are not tied to any financial contributions— you can’t pony up to obtain more power or profits.

If you’re smelling a whiff of anti-capitalism, you’d be right. In a regular business, I, a person with the means to do so, can buy a stake in your business that would grant me both more power and more profits, even if I never lift a finger towards value creation within the business.

All of the businesses we work with at Wanderwell include working owners, meaning they both own and work in the business; and while we work with cooperatives, most have non-cooperative legal structures.

It’s worth noting that the difference between a partnership and a cooperative legally can be somewhat fine, as one of the most common ways to start a worker co-op is to form a multi-member LLC and create an operating agreement and governance practices that lay out cooperative ownership4.

[

and I got into some of this on his podcast last year, take a listen here for more on the difference and how to think about one or the other structure.]This fine line is precisely why I make this proposal— a regular partnership LLC or corporation could borrow equity and profit allocation formats from the cooperative world…

How Co-ops Deal with Profits

You can maybe imagine why a worker cooperative would need a different sort of structure than the normal equity splits that dictate profit allocations— remember, worker owners receive profits based on contributions, so we can’t just allocate profit based on ownership percentages.

Here’s how it works:

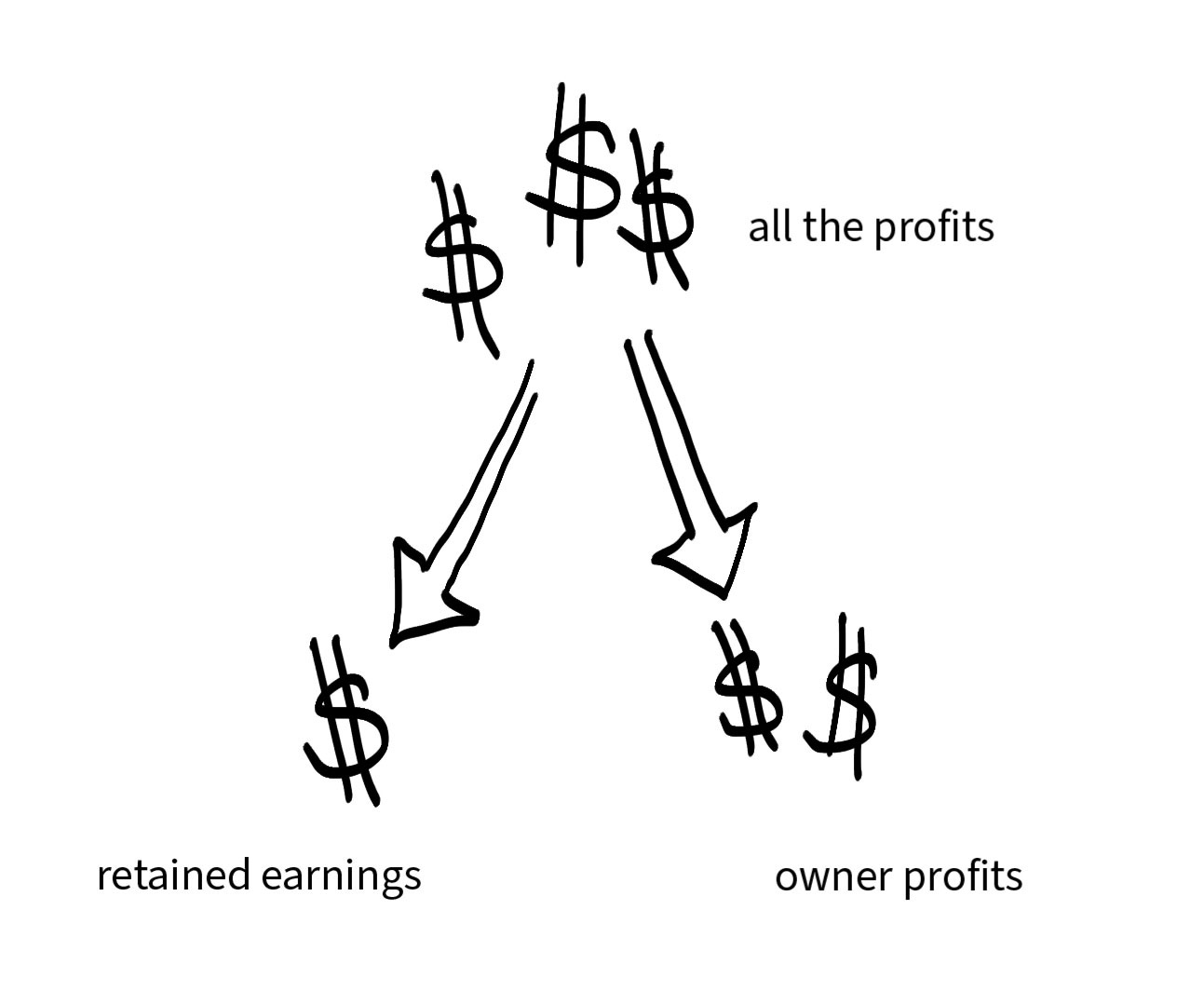

At the end of a fiscal year, we’ll (hopefully!) have a bunch of profit.

We’ll keep some for the business (“retained earnings”), the remainder will go to owners. So far, so normal.

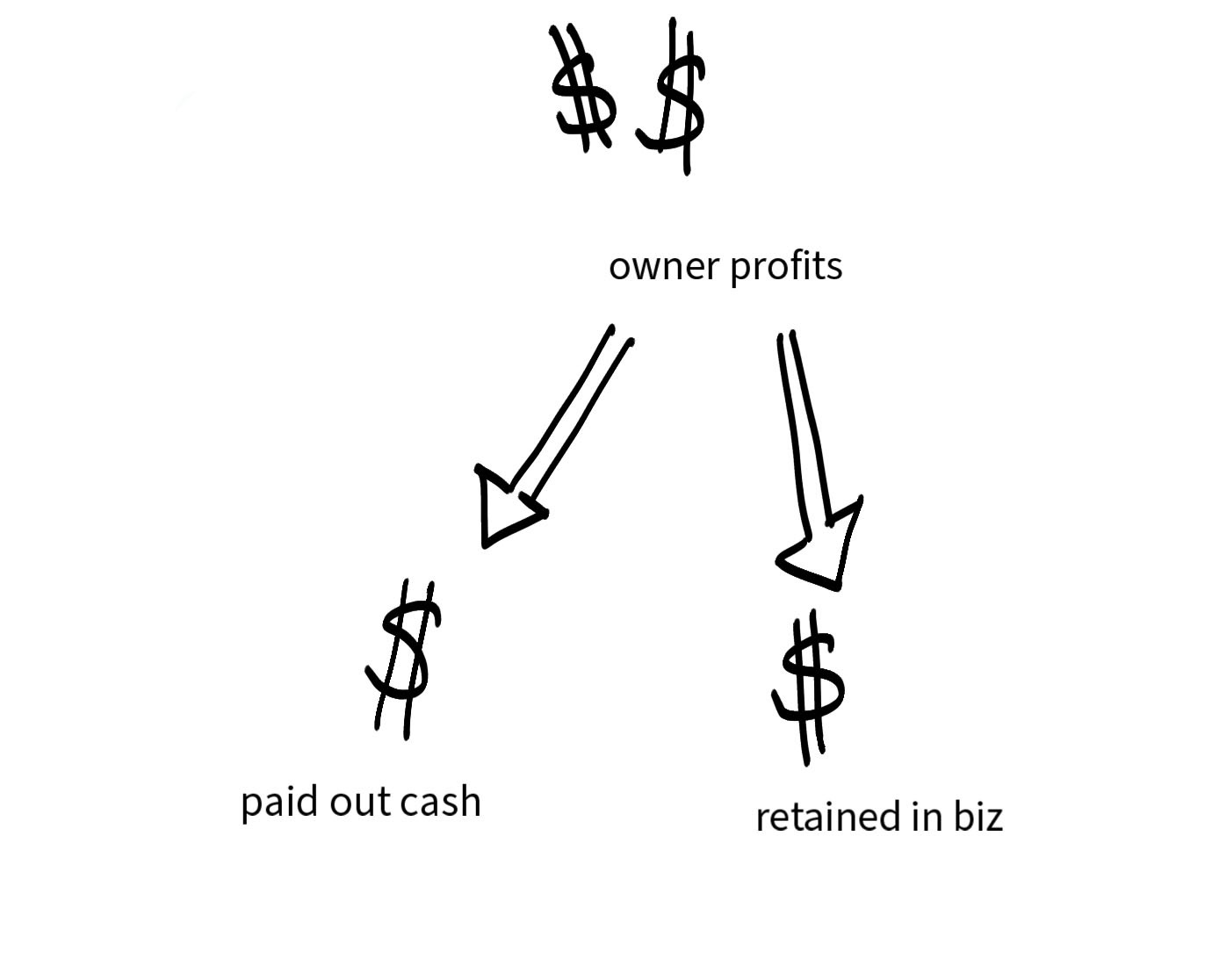

But cooperatives have an extra decision to make: how much of the owner profit pile to pay out in cash, and how much to keep in the business as worker-owned capital?5

To track worker-owned capital, cooperatives utilize special equity accounts (usually called Retained Patronage accounts). Regular partnerships have these types of accounts on their balance sheet, they’re just not used this way in practice.

Over time, your capital held in the business will (we hope!) grow. Since cash is fungible, the business can use that capital to fund business activities. Think of it like a savings account for you, the worker owner, and as a source of financing for the business.

Back to scenario #1: if we were in fact a co-op, we’ll have a system for tracking our contributions (by hours worked or value of projects completed) over the course of a year. Since I’m only working part time, my contributions and corresponding profit allocations will be less than yours, the person working full time.

Proposal #1: You, a partner in a regular old partnership could adopt this same contribution-based system of profit distribution.

In a vanilla partnership, if I don’t end up exiting, one of two things usually happens when one person scales back: we leave equity percentages as is and risk resentment. Or we shift our equity so you own more, and pay me out for the shares I’m giving up.

But what if I decide a couple years later I’d like to work full time again? I might want to revisit our equity split…and now we’re back at messy and expensive valuations and share swapping again.

Instead, we can leave our equity at 50/50, and adopt a practice of distributing profit based on how much we’re contributing, that honors our evolving lives and commitments.

Proposal #2: What if you also chose to allocate business value based on contributions over time?

Back to scenario 2: say you’re the coasting asshole partner (I know, you would never, just imagine for a sec), but this time, you’re an asshole that happens to be part of a worker-owned co-op. Through our governing processes, we apply all sorts of remedies to help you to mend your recalcitrant asshole ways, however you stubbornly persist!

We hold a vote, and unanimously oust you.

Instead of leveraging our desire to force you— the asshole—out to extract as much cash as possible before the door slams shut, we look at the Balance Sheet and point to the exact number in your retained patronage account that you’re owed. We agree on a reasonable payment schedule over time, and that’s that. We, the remaining members, pop some celebratory bubbles: thank god that asshole is gone.

Again, in a regular partnership, you could theoretically store value in capital accounts, so rather than valuing a partner’s shares based on the business valuation and equity percentage, capital accumulates over time based on contributions.

Now, I’ll pause here to again note that this isn’t accounting or legal advice. Proposal 2 is more complicated on the tax structure side and you should do some legal and tax homework. I ran it by my most trusted CPA, and his response was:

1. That’s interesting and theoretically possible to execute.

2. Partnerships are very complicated tax-wise (at which point he also listed a bunch of specific snags that might need to be dealt with and invoked the tax code…which I won’t get into here.)

3. Wow, a lot of people will not like this idea!

Wow, a lot of people will not like this idea.

A Paradigm Shift.

Most businesses in our economy exist as assets to produce value for stakeholders. Most obviously, large corporations provide dividends to shareholders and often seek to maximize profits for those with ownership stake— Capitalism 101, right?

Capitalist ownership structures allow owners of capital to extract more value than the owner contributes.

You should always get a return on your investment, right?

Even if you, a small business leader, aren’t making all that much profit from your business at the moment, these underlying beliefs run in the background and structure of the business unless you choose to build otherwise.

If you don’t sell your business, the underlying capitalist structure will come up in these moments of partnership change; legal and accounting norms will force the extraction of value. Norms allow an asshole the leverage to force a high valuation and payout, but also allow for perfectly amicable partners to get stuck over how to fairly deal with changes over time.

What I’m proposing asks you to give up the possibility of earning more than you are owed, to instead find satisfaction in reaping exactly what you’ve sown.

To treat the business as an ongoing, regenerative space of offering value and support. To receive returns based on your labor, your contributions, and to center collective success over individual wins. To question what accounting and legal norms are forcing, and perhaps to change them.

And yes, a lot of people are not going to like that idea.

Obligatory note: this isn’t tax or legal advice! You can listen to John and I discuss this idea, and I’ve run it by our CPA, but you should of course retain your own counsel.

The “norm” way to handle an exit (which we talk about in the Divorce episode) is to buy the shares of the exiting member, which requires valuing the business. Formal valuations cost some thousands of dollars and comprise a mix of actual numbers/book value and good will or intangible value…which means there’s plenty of room for subjectivity and negotiations.

Adapted from The Democracy at Work Insitute.

This is largely because state laws vary. Some states— Pennsylvania is one —allow for the formation of a cooperative corporation, but many states don’t.

I’m being a bit loose with the technical terminology, for all of our sake; this is a great overview of how cooperative accounting works. There’s also certain tax advantages only available to cooperatives regarding patronage.